By Arne Wiig and Ivar Kolstad, Special to CNN

updated 10:32 AM EDT, Thu August 30, 2012

Angola has embarked on a major reconstruction program following the end of a 27-year vicious civil war in 2002. The oil-rich country holds general elections Friday.

Angola has embarked on a major reconstruction program following the end of a 27-year vicious civil war in 2002. The oil-rich country holds general elections Friday.

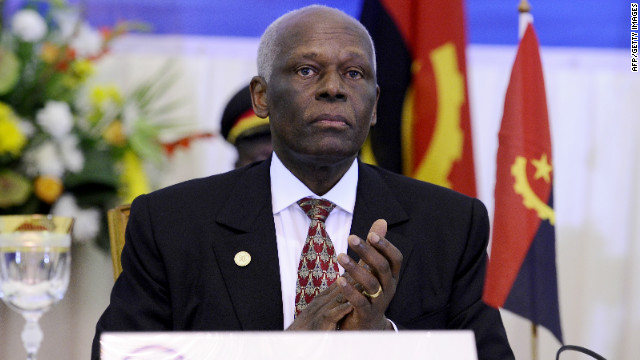

Angolan President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, 70, has been in power since 1979. Analysts expect his party, MPLA, to win Friday's elections.

Angolan President Jose Eduardo dos Santos, 70, has been in power since 1979. Analysts expect his party, MPLA, to win Friday's elections.

MPLA supporters attend Wednesday the final rally of President dos Santos in Kilamba Kaixi on the outskirts of Luanda, Angola's capital.

MPLA supporters attend Wednesday the final rally of President dos Santos in Kilamba Kaixi on the outskirts of Luanda, Angola's capital.

Thousands of Angolans take part in a demonstration in Luanda organized by the main opposition party, UNITA, to ask for free and fair elections on May 19, 2012.

Thousands of Angolans take part in a demonstration in Luanda organized by the main opposition party, UNITA, to ask for free and fair elections on May 19, 2012.

UNITA leader Isaias Samakuva (center), delivers a speech during the May 19 demonstration. The opposition has repeatedly expressed concerns about the electoral process.

UNITA leader Isaias Samakuva (center), delivers a speech during the May 19 demonstration. The opposition has repeatedly expressed concerns about the electoral process.

Dos Santos casts his ballot on September 05, 2008, at the polling station behind the presidential palace in Luanda. MPLA won the last elections with a landslide 82% of the vote.

Dos Santos casts his ballot on September 05, 2008, at the polling station behind the presidential palace in Luanda. MPLA won the last elections with a landslide 82% of the vote.

Resource-rich Angola is the second-biggest oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa, turning out more than 1.9 million barrels per day.

Resource-rich Angola is the second-biggest oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa, turning out more than 1.9 million barrels per day.

Thanks to its oil reserves, the country has posted impressive economic growth after the end of the war. It is currently the third-biggest economy in sub-Saharan Africa, after South Africa and Nigeria.

Thanks to its oil reserves, the country has posted impressive economic growth after the end of the war. It is currently the third-biggest economy in sub-Saharan Africa, after South Africa and Nigeria.

But despite the progress made since 2002, Angola remains one of the most unequal societies in the world. In Luanda, millions of people live in crowded shantytowns, like the Boa Vista slum (pictured), in squalid conditions.

But despite the progress made since 2002, Angola remains one of the most unequal societies in the world. In Luanda, millions of people live in crowded shantytowns, like the Boa Vista slum (pictured), in squalid conditions.

Angola, which has a population of some 18 million people, ranks 148th out of 187 countries in the U.N.'s Human Development Index.

Angola, which has a population of some 18 million people, ranks 148th out of 187 countries in the U.N.'s Human Development Index.  A large portrait of the Angolan President is seen in the center of Luanda on January 30, 2010. The Angolan capital was last year named the world's most expensive city for expats.

A large portrait of the Angolan President is seen in the center of Luanda on January 30, 2010. The Angolan capital was last year named the world's most expensive city for expats.

Earlier this year, Angola celebrated 10 years of the end of its civil war. Here, Luanda residents walk in front of a giant portrait of President dos Santos, with text reading "The Architect of Peace" on April 4, 2012.

Earlier this year, Angola celebrated 10 years of the end of its civil war. Here, Luanda residents walk in front of a giant portrait of President dos Santos, with text reading "The Architect of Peace" on April 4, 2012.

Angola was gripped by a brutal civil war for 27 years that led to the death of up to half a million people, according to the U.N., and also left 15.000 landmines behind.

Angola was gripped by a brutal civil war for 27 years that led to the death of up to half a million people, according to the U.N., and also left 15.000 landmines behind.

After Portugal's decision to cede power in the African country in the mid-1970s, pro-U.S. UNITA and MPLA, backed by the Soviet Union and Cuba, fought a proxy Cold War for control of the country and its vast resources.

After Portugal's decision to cede power in the African country in the mid-1970s, pro-U.S. UNITA and MPLA, backed by the Soviet Union and Cuba, fought a proxy Cold War for control of the country and its vast resources.

The war ended officially in 2002 when a peace deal was signed following the death of UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi.

The war ended officially in 2002 when a peace deal was signed following the death of UNITA leader Jonas Savimbi.

HIDE CAPTION

Angola's construction boom

President Jose Eduardo dos Santos

Support for MPLA

UNITA demonstration

Opposition leader Isaias Samakuva

2008 elections

Oil boom

Oil boom

Rich-poor divide

Rich-poor divide

Living in Luanda

"The Architect of Peace"

Vicious conflict

Vicious conflict

Vicious conflict

<<

<

>

>>

STORY HIGHLIGHTS

- Oil-rich Angola is holding its second peacetime elections on Friday

- The country has experienced strong growth in the years after the end of its civil war

- Resource-rich countries with little political accountability have trouble converting resources into development

- Business profitability among the poor is constrained by lack of education and health services

Editor's note: Arne Wiig is a Senior Researcher at the Chr. Michelsen Institute (CMI) and coordinator for its research cluster "Poverty Dynamics. He has undertaken long−term fieldwork in Angola, Namibia and Bangladesh. Ivar Kolstad is Research Director at CMI, focusing on poverty dynamics, natural resources and development and corporate social responsibility.

(CNN) -- Ten years after the end of its civil war, Angola, which is heading to the polls Friday, has been transformed into a regional African power with a strong economy, but poverty is still widespread.

Angola experienced double digit growth in GDP annually in the period 2002-2008. In the last five of these years, average annual growth was at 17%, which more than doubled the size of the economy. The country is the second largest oil producer in sub-Saharan Africa, and the third biggest economy, after South Africa and Nigeria.

Do these tremendous growth rates mean that Angola has escaped the so-called resource curse, where oil resources are detrimental to growth? Is Angola likely to continue growing at these fast rates, and perhaps catch up to the largest economies in the region in a few years' time? Is Angola a success in terms of development and poverty reduction?

It is not uncommon for countries that come out of a civil war to grow at very high rates. The growth seen in the period 2002-2008 may thus reflect the end of the civil war in 2002.

Read related: Post-war generation emerges as Angola votes

Arne Wiig

If there is a tendency to blame all that is wrong in Angola on its war legacy, perhaps the end of the war should be credited for things that have been going well?

It is always problematic to speculate about future growth rates. After 2009, growth has dropped to around 3% per year and projections for the coming years are in the range 5-8%. There are many reasons for this significant drop, the financial crisis and oil price development are part of the explanation.

But in the longer perspective, there may be more fundamental structural challenges to Angolan growth and development. In particular, research shows that resource-rich countries with little political accountability have trouble converting resources into development.

Angola scores still low on governance indicators, and the coming elections seem unlikely to challenge the over 30-year-long reign of President Jose Eduardo dos Santos.

Ivar Kolstad

Watch: Angola's economic potential

The fact the Angolan economy is the most concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa also makes growth vulnerable. The profitability of the oil sector renders diversification difficult in any economy.

But is the Angolan government really trying to diversify?

An important question is how government reliance on oil rents affects political incentives to diversify the economy. Business environment indicators for the country remain poor, while investment is hampered by a lack of education and institutional challenges.

Do the poor care about the overall growth rate of the Angolan economy? Experience shows that growth reduces poverty less in countries with high initial inequality. And oil-driven growth in a country with low political accountability is susceptible to wealth concentration rather than redistribution. Employment in the oil sector is typically also too limited to produce widespread economic opportunities.

Read also: Ghana's oil discovery: blessing or curse?

We really don't know too much about the situation of the poor in Angola today. The last real census in the country was conducted in 1970. The last figures on poverty are from 2000, putting the proportion of people living on less than $1.25 a day at 54%. Angola ranks as 148 out of 187 countries on the Human Development index.

Based on a household sample, INE estimated a poverty rate of 37% in 2008. However, it is difficult to assess how the poverty line was constructed. As data is not directly comparable to previous studies, it is also problematic to analyze development over time. In spite of this, the President claims that the poverty rate has been reduced from 70 to 37% from 2002 to 2008.

A census is due to be held next year. Interestingly, but perhaps not surprisingly, it takes place after the coming elections.

Some data of a more limited nature do provide a window onto the situation of the poor in Angola. In 2010, the Angolan NGO Development Workshop and the Chr. Michelsen Institute conducted a survey of microcredit clients in Luanda.

Results suggest that business profitability among the poor is constrained by a lack of education and health and by corruption. This indicates that the factors that restrain dynamism in non-oil segments of the Angolan economy, also act as constraints on the very survival of the urban poor.

Without structural and political reforms of these constraints, it is hard to believe that an election in and of itself will change the lives of the poor.

The opinions expressed in this commentary are solely those of Arne Wiig and Ivar Kolstad.

No comments:

Post a Comment